We often hear directly from scientists about the positive impacts they get from engaging with our enthusiastic and diverse audience of school students. We’ve been able to research these impacts in more depths as part of the ChallengeCPD@Bath project run by the University of Bath. This in turn is part of the Strategic Support to Expedite Embedding Public Engagement with Research (SEE-PER) project funded by UK Research and Innovation.

We looked at whether taking part helped scientists from the March 2018 event improve their communication skills and if so, explore why IAS worked as experiential training. The results showed scientists became more confident communicating with public audiences and helped them develop effective ways of talking about their work. The opportunity for frequent practise, honest student feedback, and the text based nature of interaction were among the elements highlighted by scientists as particularly helpful.

Using these results we can demonstrate I’m a Scientist is effective experiential training in public engagement, especially for scientists with less experience or lower confidence. We’ve already incorporated some of the evidence into new materials explaining the value in taking part. The strongest evidence currently comes from the qualitative research and we can look at ways of more effectively assessing the positive impacts through quantitative data.

Read more about the results and methods for the elements of the research:

We’d like to thank Dr Helen Featherstone and the team at University of Bath Public Engagement Unit for the opportunity to be part of the ChallengeCPD@Bath project. Find more information on the other outcomes of the project at the Public Engagement Unit blog.

Taking part improves the confidence of scientists communicating their work to public audiences

Anecdotally, we often hear that taking part gives scientists a lot of confidence when talking about their work. We decided to 1.Ask scientists about their confidence before and after the event, and 2. See if tracking how they felt each day might reveal more evidence of experiential learning.

We asked scientists to score their confidence communicating with the public each day of the event. We hypothesised that once scientists started the event and had a go at actually talking to the students their confidence would dip, before increasing again as they became better at handling fast paced live chats and imaginative ASK questions.

Out of a possible 517 scores, the scientists submitted 414, with scores from 37 scientists submitted each day on average.

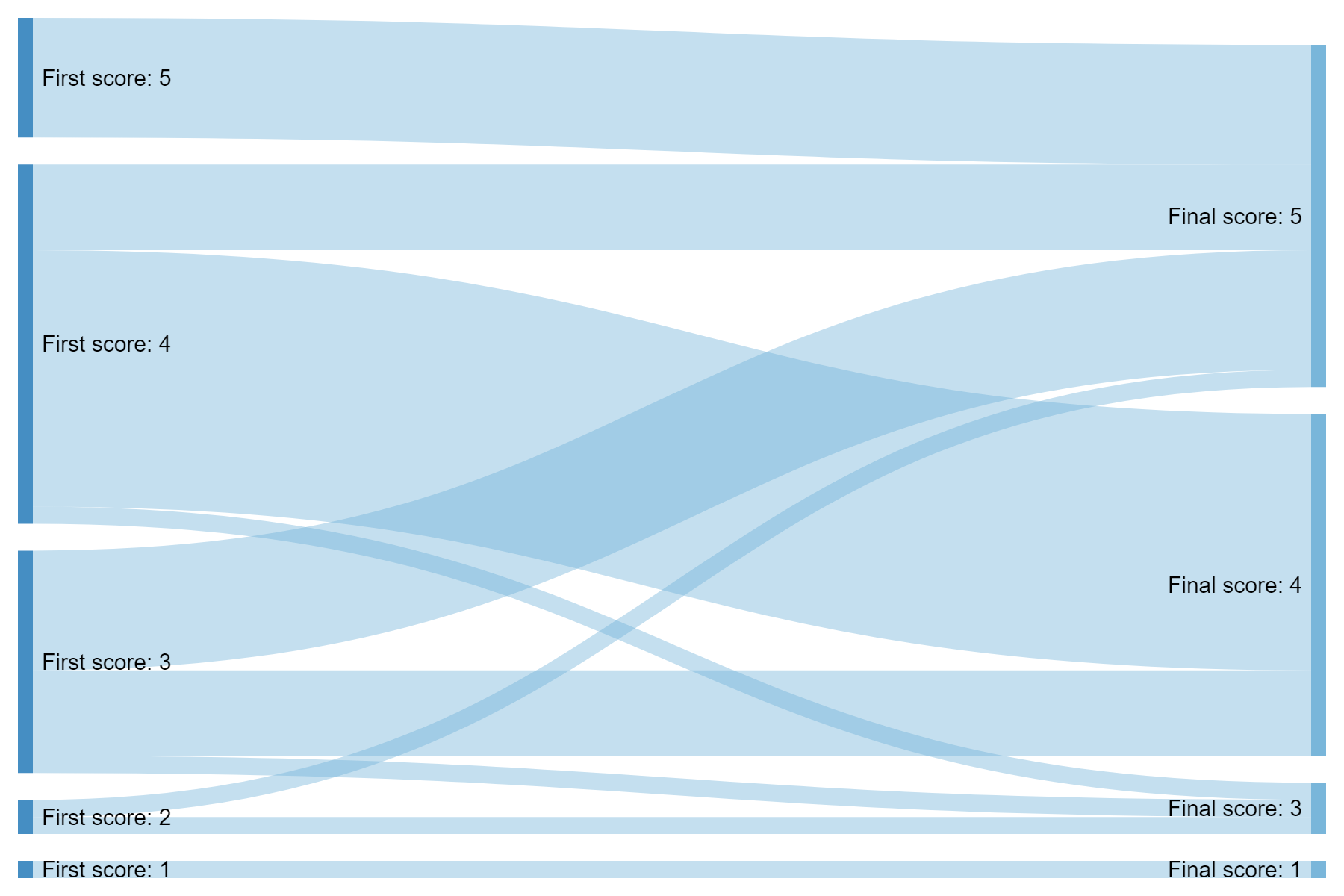

The distribution of final scores submitted by scientists compared to their earliest score, either from before, or in the first week of, the event.

Overall, there was a clear improvement in the scores submitted after the event. For example, 91% of scientists scored themselves at 4 or higher post-event and, in particular, 44% scored themselves at 5 (very confident) post-event, compared to just 13% beforehand.

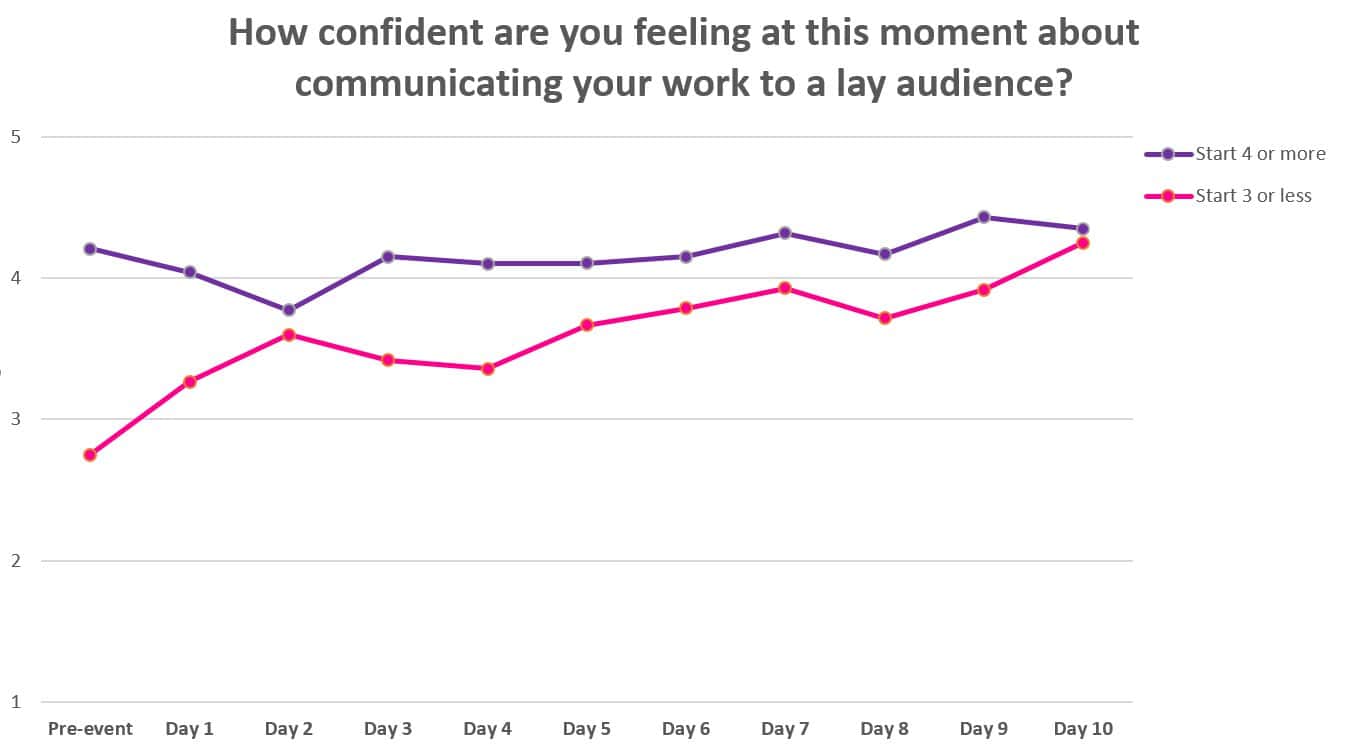

Day to day, there wasn’t a dramatic dip then increase. However when split into two different segments, a clearer pattern could be discerned:

- Those less confident (3 or less) at the start grew the most as the event went on.

- Those more confident (4 or more) at the start became less so once the event started, before becoming more confident again in the following days.

Judging by the comments submitted with scores, it could be that Group 1 contained people who had done little public engagement beforehand, whereas Group 2 could include those who were more experienced.

Both groups finished with almost exactly the same score, suggesting the experience was beneficial no matter where you started. A couple of scientists also noted that being evicted had decreased their confidence slightly.

The scores also suggest women gain confidence at a faster rate than men. The confidence of female scientists increased on average by 27% during the event (3.52→4.45), compared to an increase of 10% for male scientists (3.76→4.13).

2. Quantifying skills improvement using one sentence descriptions is difficult

Every scientist who applies for IAS must submit a sentence that describes what they do. These are then judged by students and teachers and the average ratings are used to help guide who gets places in each event. We wanted to see if the ratings increased for the sentences written post-event, and if their readability had increased indicating that the scientists were better at communicating what they do.

35 scientists submitted a post-event sentence to compare with their pre-event sentences.

Student/teacher ratings: The average for post-event sentences was 0.77, compared to a pre-event average of 0.90, representing a decrease in rating of 0.13

Readability: The average grade for post-event sentences was 9.23, compared to a pre-event grade of 10.32, representing an increase in readability of 1.09 grades.

The results do not suggest any clear conclusions. The decrease in student ratings, although indicating that the sentences were likely not as good, is very small. Likewise, the increase in readability is too small to infer impact. Subjectively, there is a sense that less exciting language has been chosen in the post-event sentences in favour of conciseness.

This could indicate either:

- Scientists do not become better communicators through the event

- This is countered by hundreds of scientists reporting increases in their communication skills and continued use of effective phrases developed in the event.

- Other factor(s) influenced the test, for example, the motivation to impress the students was missing after the event had taken place.

- If run again, we could provide a reward for the best rated post-event sentences to match the pre-event motivational condition. However, it may be hard to replicate the incentive provided by the opportunity to take part in IAS.

3. The format enables and encourages scientists to develop their communication skills

Hearing from the scientists interviewed, it was clear that all five believed taking part in I’m a Scientist had improved their skill in communicating with the public. Read the full narrative for each interview.

In summary, benefits mentioned were:

- Being able to better adapt their language to their audience (avoid jargon and technical language)

- Developing succinct phrases and effective analogies to explain concepts that they continue to use

- Getting better at explaining the wider relevance of their research to get people engaged, even if they had had lots of previous outreach experience.

- Positive impacts on how they communicated in professional contexts.

- More confidence when communicating, especially for those with less outreach experience. All had taken part in further outreach activities following the event in March.

The format of I’m a Scientist was particularly helpful for the scientists in the following ways:

- Frequent practice – Daily chats and ASK questions over two weeks allowed for new ways of explaining to be tested out and phrases to be honed over time

- ‘Two-way’ – Student feedback in the form of further questions let scientists gauge how well they were communicating

- Online and text-based – Students gave more honest responses than some scientists had experienced in person, scientists felt more comfortable answering challenging questions.

- Shared experience – Scientists could see and learn from how others in their zone approached answering the students

“…every time I was answering to the kids they would ask more and more and like that would sort of bring, break down the concept into basics and I understood that that is how you can explain your work to a non-specialist audience” Kezia, PhD Student, no previous outreach experience

“Some of the analogies I totally plagiarised from the students! They come up with their own ways of understanding what you do. You’d describe it and they’d say ‘oh, is that a bit like this?’ and you’d say ‘exactly’. And that’s really nice too, when they do the imaginative work of explaining it for you. I really liked that.” Max, PhD Student, some outreach experience.

“I think I’ve learned how to be more ‘less specific’, how to maybe explain more of the sort of bigger picture of where my research could go and then discuss into more details from there depending on if there’s interest. I think that helps people who don’t understand in technical terms more what I’m more what you’re doing if you sort of say well this is the end goal” Neil, Postdoctoral researcher, experienced in outreach

“It put in my mind that I can be asked any question outside my field that I don’t expect… I would do my best to answer those questions. And if I don’t really know something, I wouldn’t be afraid. I would say ‘Ah I’m sorry I don’t really know about this’ And I could say ‘What do you know about this?’” Walaa, PhD student, some outreach experience

“Now I feel I can, you know I’ve got that you’re in the lift and they’re getting out on the second floor speech….Because you’re not in person… there’s not that level of politeness, it’s just ‘I’m not interested anymore, bye, I’m going to speak to someone else’, rather than feeling like they’re stood in front of their teacher, or their mum and dad and feeling like they have to be polite to this person they are talking to… I kind of think it makes you have to get better.” Aileen, PhD Student, experienced in outreach

4. Methods

Scoring confidence in communicating

A short survey was sent to every scientist on the Friday before the event asking them to score themselves from 1(Not very confident) to 5 (Very confident) in answer to the question ‘How confident are you feeling at this moment about communicating your work to a lay audience?’. There was also an open text field to record their thoughts on how they had arrived at that score.

The scientists then received the same question every weekday at 4pm during the event until the final Friday. This gave us a maximum of 11 responses for each scientist. Reminders were also sent first thing each morning in case they had missed the previous day’s email.

Rating scientists’ sentences

Students are asked ‘Should this person get a place in the next event?’ and then rates each sentence either Definitely not, Maybe not, Probably, Definitely! We then assign these options a rating from -2 to +2 to give an average rating for each sentence.

In March, we asked the participating scientists to write a new sentence describing their work after taking part and compared its average rating to that of the sentence they submitted in their application. Each sentence was rated an average of 18 times. We also processed the sentences individually through an online readability scorer using the Flesch-Kincaid test. In this test, the lower the score, or ‘grade level’ the more readable the text is.

Interviews

We carried out recorded phone interviews with a targeted sample of five of the scientists. We biased towards PhD students who have more to gain from training, and included people with varying levels of PE experience.