Some say there are no new ideas, just new interpretations of old ideas: primary school students designed the Blackawton Bees paper with the help of a parent scientist; citizen science runs online at scale with Galaxy Zoo; the BBC, with Terrific Scientific, help primary schools conduct their experiments.

There is an idea missing in this panoply: School students helping to design and run a new experiment at scale.

In March 2017 we ran the Wellcome funded Enquiry Zone, a zone created with one fundamental question: Could we use an I’m a Scientist zone to give hundreds of school students the chance to help design an experiment, which they could then carry out themselves?

Yes, we could. And what’s more, it’s clear there is value in giving students input at all stages of the project. It gives students ownership over research, and they gain real insight into how science works.

What happened

1. Students questioned five scientists, and chose the project they wanted to carry forward

Ideas for projects covered research on lung capacity, health apps for smart phones, animal behaviour, and nutrition. Students asked questions about the projects, and discussed their own advice and suggestions with the scientists. After all, the students were the experts on what would work in their schools.

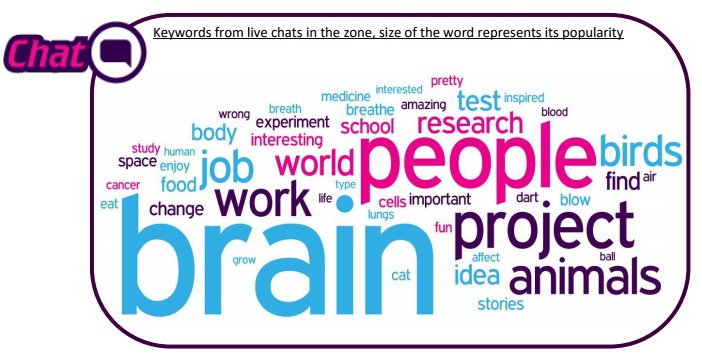

In both CHAT and ASK, the scientists research project ideas were of keen interest, with “project” being a common topic for discussion in live chats, and in ASK, there were many more questions about “research ideas” than on any other topic.

Word cloud showing popular topics in live chats in the Enquiry Zone. Read the full zone report here, or click the image [PDF]

The class had done a lot of work in March, discussing the different proposed plans, and they were happy when Sallie won because the nature and biology ideas were similar to things they had already done.

— Jenn, Teacher at Doonfoot Primary School, Ayrshire

2. Students helped design the final experiment

Students and teachers reviewed the draft experiment plans and fed back ideas. One teacher reported that their school is “big on school values of fairness, respect, equality.” The students discussed the ethics of getting a fellow pupil to judge someone on their appearance. To address this they suggested holding an assembly to explain the project to their classmates and research subjects, after working out the results for their school. This suggestion was then incorporated into the final lesson plans for all schools.

They liked the interaction with the other classes and the responsibility, they liked coming up with stories, they loved the creative bit, it wasn’t just them being told this is how you do it, they had independence.

— Sue Grubic, Teacher at St Mary’s Catholic Primary School, Lincolnshire

In the experiment, the student scientists came up with some brilliant stories; nice things such as the person they were judging was a very thoughtful friend, someone who always eats lunch with new students and and makes sure they are not lonely, or someone who used her pocket money to pay the vets bills for an abandoned puppy. Suggestions of ‘not nice’ traits included kicking over a chair and swearing at the teacher, bullying, and picking her nose and eating it.

Interestingly all of the bad stories had examples of [the subject] losing her temper and being violent or destructive. This is clearly something that all of the children recognised as something that is unattractive in someone.

— Sallie

3. Three schools took part in the research stage

Often, more complex citizen science projects such as Enquiry Zone take place within one school. Here, the online factor allowed feedback and results to be collated from multiple schools across the UK — Doonfoot Primary School in Ayrshire, Irchester Community Primary School in Northamptonshire, and St Mary’s Catholic Primary School in Lincolnshire all sent in their results.

We would have liked to see more schools take part after the first Zone in March; more registered interest but ultimately did not take part in the experiment. In future we will look for ways to increase this uptake.

4. 138 students conducted the experiment, interviewing 236 of their classmates

One school reported that the project gave them lots of opportunities to discuss the ethics of research, as well as discussions around whether people should do things because an adult in authority told them to. The senior management team at the school have seen the experiment and results and they planned to use it this year with the whole school as a topic to discuss making judgments on people.

The children were really enthusiastic about it, they felt it was a special experience … It felt real to them, It was something we would never normally do.

— Jenn, Teacher at Doonfoot Primary School, Ayrshire

One student said:

Its inspired me to know that I could be a scientist and do this.

Tweet by Tracy Tyrrell, teacher at Irchester Community Primary School, Northamptonshire

5. The results were significant and in part surprising — The research will be submitted for publication

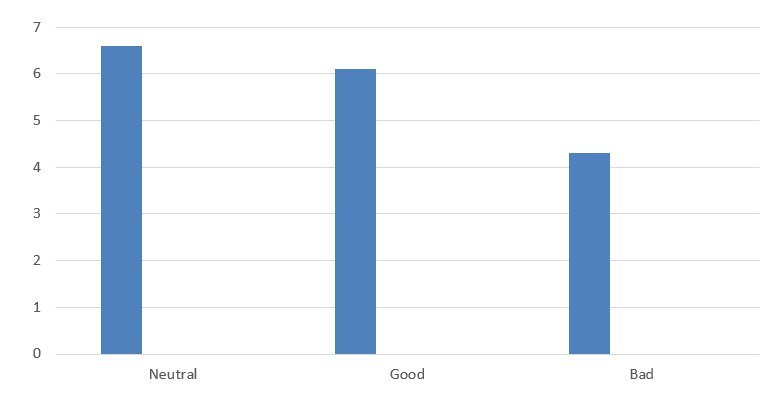

Sallie and the students discovered that when you hear something nice about someone else it doesn’t really change how you think they look. However, hearing about negative traits does influence the judgement of the person’s looks. Interestingly, they showed that the stories with the most negative impact were those with a “yuk factor”.

Ratings of attractiveness after no information, after hearing good things, and after hearing bad things. Full results

The results were written up and send back to the teachers and students. See the results here.

Sallie is now finalising the manuscript of her report and plans to have it submitted to a journal in the next few weeks.

If you have an idea for a project you would like to run with us — citizen science or otherwise — get in touch! Leave a comment below, or email Shane at shane@mangorol.la.