We’re thinking increasingly about Science Capital and how we apply it to our projects. It is a powerful concept that resonates strongly with what we aim to do and we want to make sure our projects make as much of a positive contribution to young people’s Science Capital as they can. We are looking for ways to evaluate in relation to Science Capital to show whether we are achieving this.

What is Science Capital?

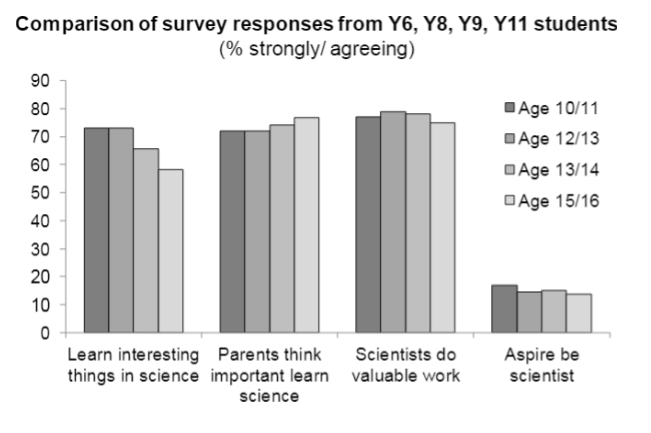

If you’ve read the 2013 ASPIRES report you’ll be familiar with this striking graph showing that although nearly 80% of UK students value science, less than 20% aspire to be scientists. Why is this?

Graph courtesy of ASPIRES/ASPIRES2: ucl.ac.uk/ioe/departments-centres/departments/education-practice-and-society/aspires

Based on their research, the ASPIRES team have developed the concept of Science Capital; the combination of experiences, personal connections, knowledge and attitudes that contribute to how much a young person identifies as a “science person”. The researchers found that young people with high Science Capital are more likely to have science-related career aspirations than those with lower Science Capital.

kcl.ac.uk: Dimensions of Science Capital

The ASPIRES researchers identified eight dimensions of Science Capital. We’ve summarised them below. For more detail follow the link to the Enterprising Science site.

- Scientific Literacy

A young person’s knowledge and understanding about science and how science works. This also includes their confidence in feeling they know about science.

- Science-related attitudes, values and dispositions

The extent to which a young person sees science as relevant to everyday life.

- Knowledge about the transferability of science

Understanding that science qualifications, knowledge and skills have broad applications and are useful for a wide range of jobs beyond and not just in science.

- Science media consumption

Engaging with science content in the media (books, television, or on the internet).

- Participation in out-of-school science learning contexts

Participation in, e.g. science museums, science clubs, fairs, etc.

- Family science skills, knowledge and qualifications

Having family members with science qualifications, skills, and interests.

- Knowing people in science-related roles

Knowing people in their community who work in science-related roles.

- Talking about science in everyday life

How often a young person talks about science out of school and the extent to which they are encouraged to continue with science.

Science Capital and I’m a Scientist

Our data and experience suggest that taking part in our I’m a … events has a measurable impact on students’ attitudes towards science and make a positive contribution to young people’s Science Capital.

We’ve looked at the 12 dimensions of Science Capital listed above and thought about whether and how I’m a Scientist contributes to each. There are three dimensions where we think our contribution is – or should be – most significant: knowing people in science-related jobs, scientific literacy, and knowledge about the transferability of science.

Knowing people in science-related jobs

Description: The people a young person knows (in a meaningful way) in their family, friends, peers and community circles who work in science-related roles.

We had a lot of discussion about whether the interactions between young people and scientists during I’m a Scientist, qualify as knowing someone “in a meaningful way”. Ultimately, we felt that while our events don’t fully fit the description, they fit the spirit, and – we think – make a small, though convincing contribution.

In fact, this is the area where we think our projects are most distinctive among STEM interventions. Young people who take part, engage in sustained and enthusiastic interactions with a group of real STEM professionals. Some students even form opposing teams to support their favourite scientist!

@oojeyboojey @aaronbroadley @imascientist Team Natalie vs Team Aaron pic.twitter.com/dpO9sBbgQY

— ArdAcad Physics (@ArdAcadPhysics) November 20, 2015

How we contribute:

- Through voting, young people…

- Take time to consider what is important in making a good scientist

- Learn about scientists by reading their profiles and deciding who to vote for

- Make personal judgements based on their direct interactions with the scientists and choose favourites

- Through ASK and CHAT, young people…

- Hear about scientists’ motivations and achievements

- Learn about scientists’ interests, likes and dislikes, and find areas in common

- Hear about life as a scientist from scientists’ points of view

- Through the whole process, young people learn that many different types of people become scientists

Scientific literacy

Description: A young person’s knowledge and understanding about science and how science works. This also includes their confidence in feeling that they know about science.

We see plenty of evidence that suggests we contribute to this. Students ask scientists and engineers a huge variety of questions about science and how science works. In addition, we hope that the student-led approach and the willingness of scientists and engineers to answer pretty much any question gives students more confidence that they know about science.

How we contribute:

- Scientists answer questions on scientific topics and students learn from their answers

- Students learn about scientific process, ethics, and science in society

- Young people develop their confidence in feeling that they know about science as they ask questions

Knowledge about the transferability of science

Description: Understanding the utility and broad application of science qualifications, knowledge and skills used in science (e.g. that these can lead to a wide range of jobs beyond, not just in, science fields).

Knowledge about the transferability of science is a really important dimension, and one where we should be able to make a contribution. At the moment, we are concerned we’re not getting it quite right.

We have run the occasional zone with candidates who have a science background but work in other roles, but in general zones tend to comprise only practicing scientists or engineers. We’re concerned this reinforces the “science = scientist” idea rather than helping students see that science skills are transferrable.

We’re working on evaluating whether our concerns are justified, and how we could adjust the composition of future zones to improve things.

Next steps

We’re just at the start of this process of evaluating projects in relation to Science Capital. As mentioned above, the process has already made us think about how our I’m a… projects contribute to young people’s knowledge about the transferability of science.

We’d really welcome discussion about this to help us develop our thinking so please get in touch and share your thoughts, either in the comments below, or elsewhere.

As a final note, there are also a few Science Capital dimensions where we don’t have much influence, and one – science-related attitudes, values and dispositions – where we think we do contribute, but would find it hard to evidence.